How a Young Couple’s Home Deposit Was Stolen by Scammers

Most people think it’s only old people who get scammed, but property fraud threatens younger Australians who already face an uphill battle to enter Australia’s expensive housing market.

In 2023, with a baby on the way and dreams of settling down, Hope and Tom Clifford were full of optimism. They’d found the perfect block of land outside Dubbo, NSW, and were ready to build their forever home.

Like many Australians, they trusted that the property settlement process — though complex — would go smoothly.

They had done it before. But a single, convincing email changed everything.

The fraudulent payment misdirection email that not even the banks could spot as a scam.

The couple received what appeared to be a routine message from their solicitor asking them to deposit their $250,715 settlement funds into a bank account.

They printed the instructions and went inside their local NAB branch to make the transfer. With receipt in hand, they even sent confirmation back to their solicitor — who only later advised the couple that they hadn’t received the funds.

Three weeks later, confusion turned to horror.

The real solicitor asked where the money was. The solicitor’s email account had been hacked. Scammers had infiltrated the conversation and sent Hope and Tom a fake invoice, redirecting their life savings into a criminal’s hands.

“We had no idea that professional scammers were targeting conveyancers and lawyers,” says Hope. “Everything about the email looked normal. It used the exact same thread we’d been communicating on.”

Trying to get justice for his scam was even harder than uncovering who was behind the crime committed against him.

Regulators and complaints bodies offered little to no support.

Scam and cybercrime warnings are buried on websites that don’t explain how the impersonation and con happens.

The banks hide the details of where money goes once transferred, until police and law enforcement step in to subpoena the details, which takes months.

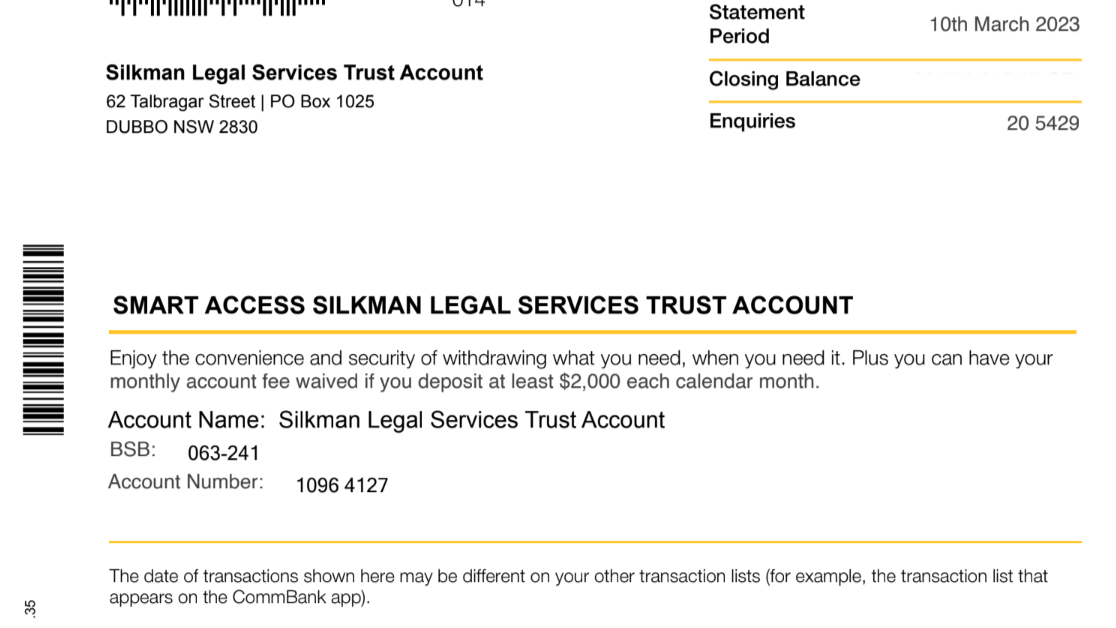

Property settlement frauds like the one the Cliffords experienced are a Business Email Compromise (BEC), a sophisticated and increasingly common form of cyber-enabled real estate fraud. Their payment was siphoned into a Commonwealth Bank “mule” account — controlled by criminals to launder stolen money.

It took the Cliffords nearly two years to get justice, and even then the Australian Financial Complaints Authority offered them only 70% reimbursement after months of convincing them to take less money and settle the matter quickly.

“Not only did we lose our savings,” Hope explains, “we were made to feel like it was our fault. The bank blamed us. We spent over $10,000 on lawyers just trying to understand what rights we had — because no one could tell us.”

“These scams are so advanced. They prey on trust.”

Scam Victim Alliance president Harriet Spring says this experience is all too common. “We don’t blame victims when someone smashes their window and steals their car,” she says. “But because scam crime is invisible, victims are blamed — not helped.”

Eventually, after intense advocacy and support, Hope and Tom won a panel determination from the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA). NAB was forced to repay 70% of their loss.

“It was gruelling,” says Hope, “but we were determined to see it through — not just for us, but for other home buyers. We now know there are many victims like us, and most never get a cent back.”

Their mule Mark Freeman did a deal for $5000 on Snapchat to rent his bank account for the scam

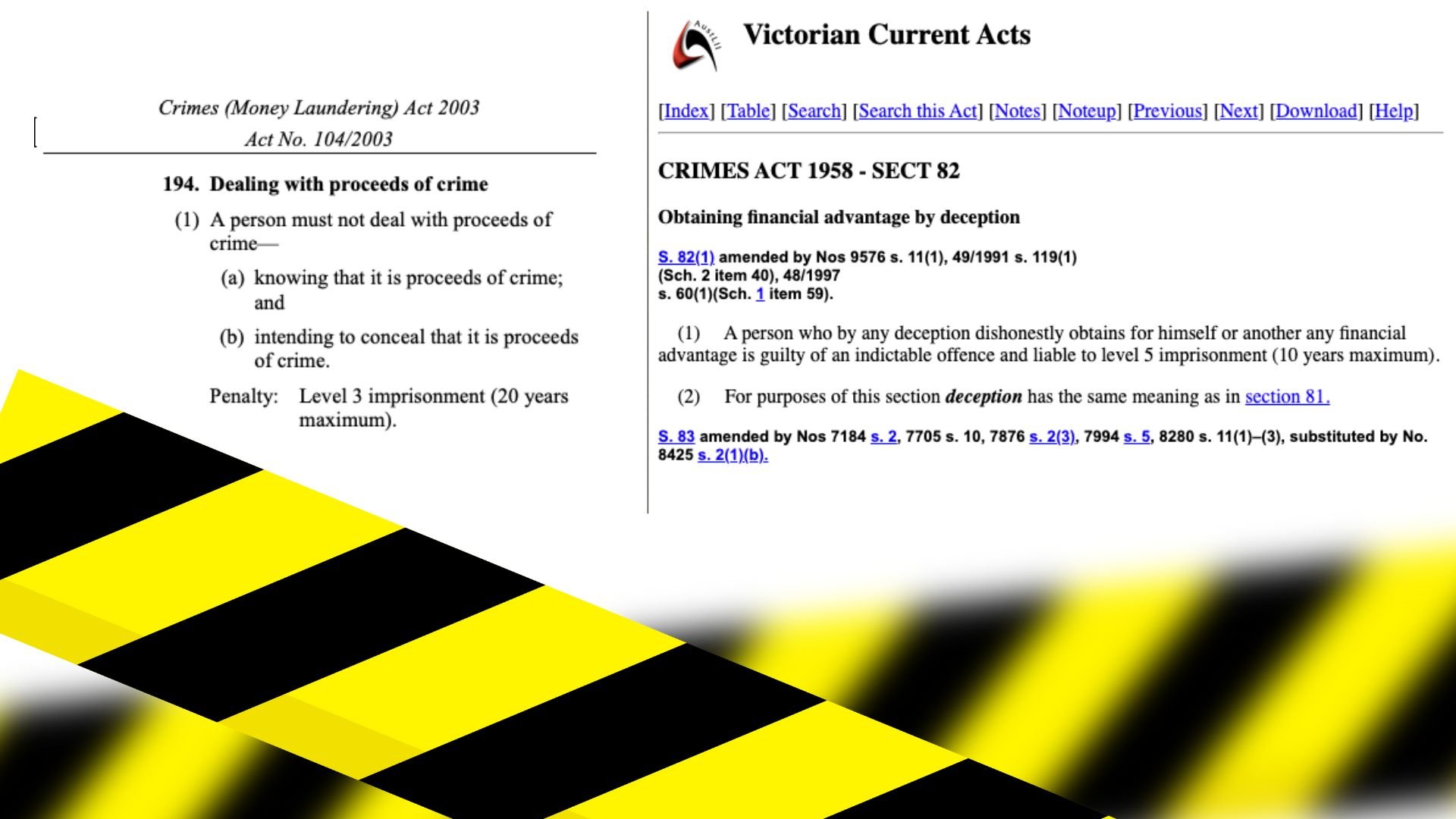

The Melbourne man who used his Commonwealth Bank account to steal Hope and Tom’s stolen money was charged with recklessly dealing with the proceeds of crime but received just 150 hours community service with no conviction recorded.

The court heard that Mark Freeman, who lived in Weir Views, did the deal to steal Hope and Tom’s over Snapchat and was supposed to be paid $5000. AS soon as the money was transferred, he was driven around Melbourne withdrawing cash, buying foreign currency and a $94,000 gold bar. Mark Freeman told the court he never received his $5000 payment.

All the money was laundered on the streets of Melbourne within one day. Commonwealth Bank never closed down Mark Freeman’s bank account either.