SVA Speaks out about scam prevention framework codes

Scam Victim Alliance spent our Christmas holidays writing this submission to Treasury about it’s world-leading reforms to fight scams. The SPF risks becoming a framework of good intentions that will actually increase scam harms unless the Codes impose clear and enforceable obligations on regulated entities

Executive summary

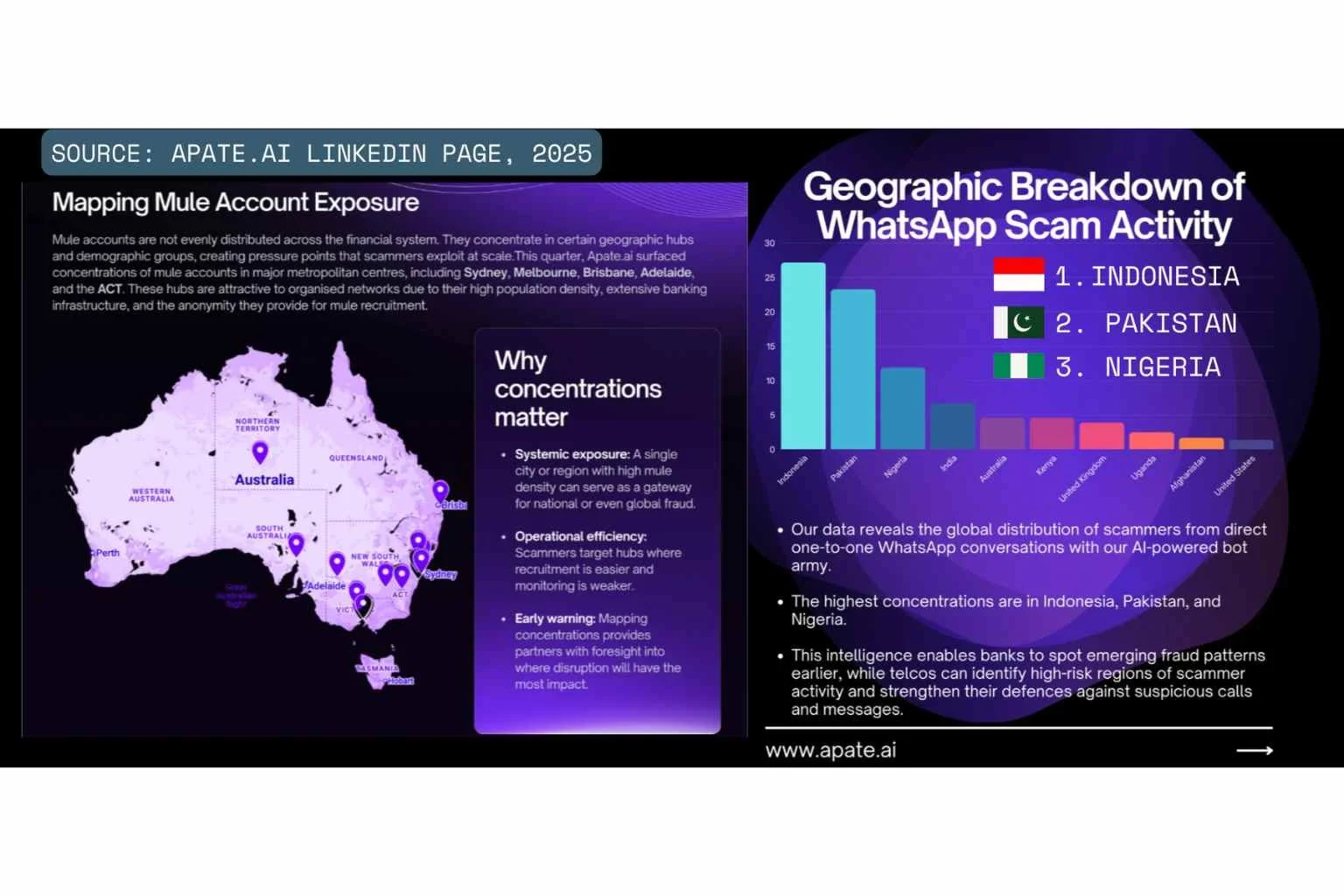

Our lived experience gives us deep insight into how scammers manipulate digital payment systems — and how banks, telcos, and digital platforms have allowed their infrastructure to be weaponised. Australian corporations are unwittingly funding what Interpol has called a “global crisis” of human trafficking and other criminal harm. We welcome this opportunity to make a submission to the SPF Treasury consultation.

Scam Victim Alliance (SVA) was founded in May 2025 to support Australians devastated by scam frauds, abandoned by a system that delivers inconsistent recovery processes and untold trauma.

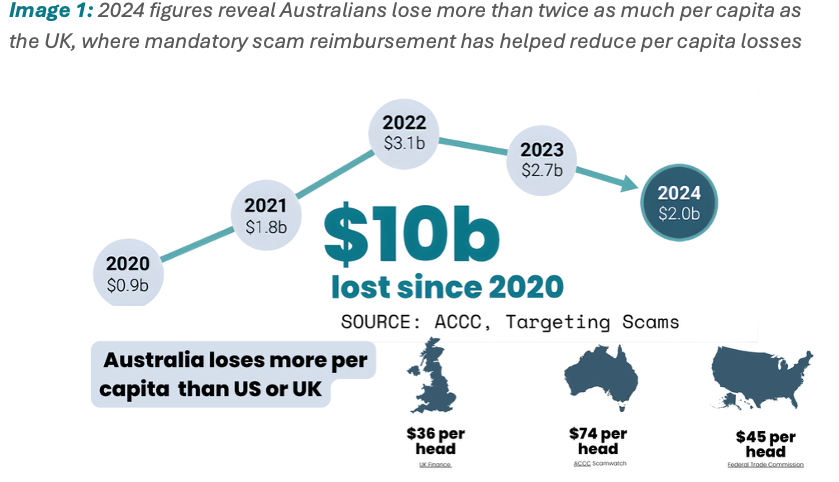

Scam fraud hits hardest in Australia’s most vulnerable communities—older Australians and those from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds—forcing taxpayers and individuals to carry the cost of the escalating scam fraud crisis harming all nations around the globe. Australia now faces scam compounds setting up shop on its doorstep—in Timor-Leste, New Guinea, Palau and Fiji, no doubt attracted by the rich pickings of Australia’s poorly protected payments markets.

We believe that if the clear recommendations from the 2019 Banking Royal Commission into Misconduct in the Banking, Superannuation and Financial Services Industry had been successfully implemented and enforced by APRA and ASIC, much of the scam-related harm experienced since 2020 could have been significantly reduced, as detailed in Appendix A. If scam losses and their downstream impacts were properly accounted for, the true cost to taxpayers would be staggering.

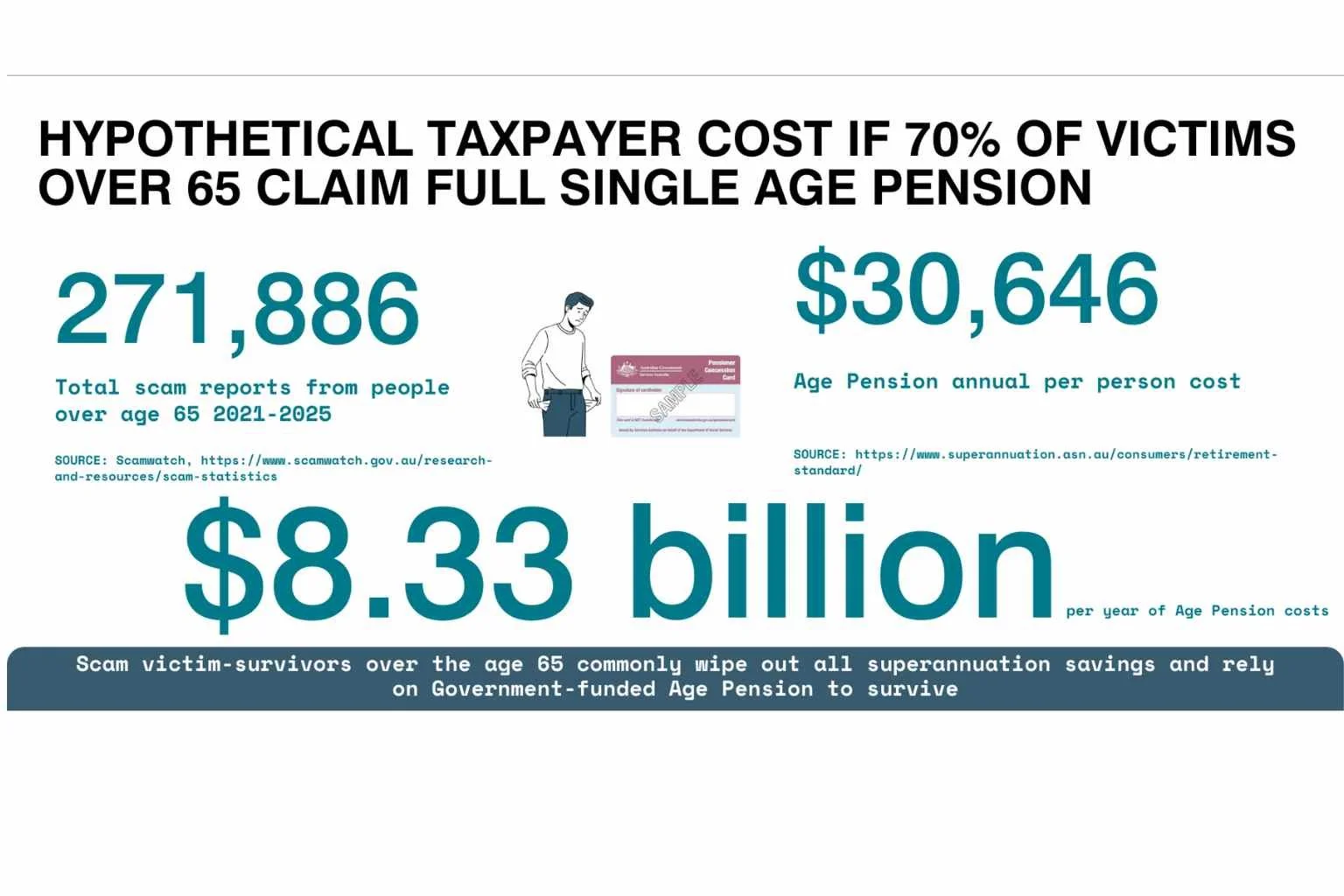

For example:

● Since 2019, 272,000 Australians over 65 have lost their superannuation to scams. If just 70% of these people had to then claim an Age Pension due to not having any superannuation, this would add an estimated $8.33 billion annually to Aged Pension costs.

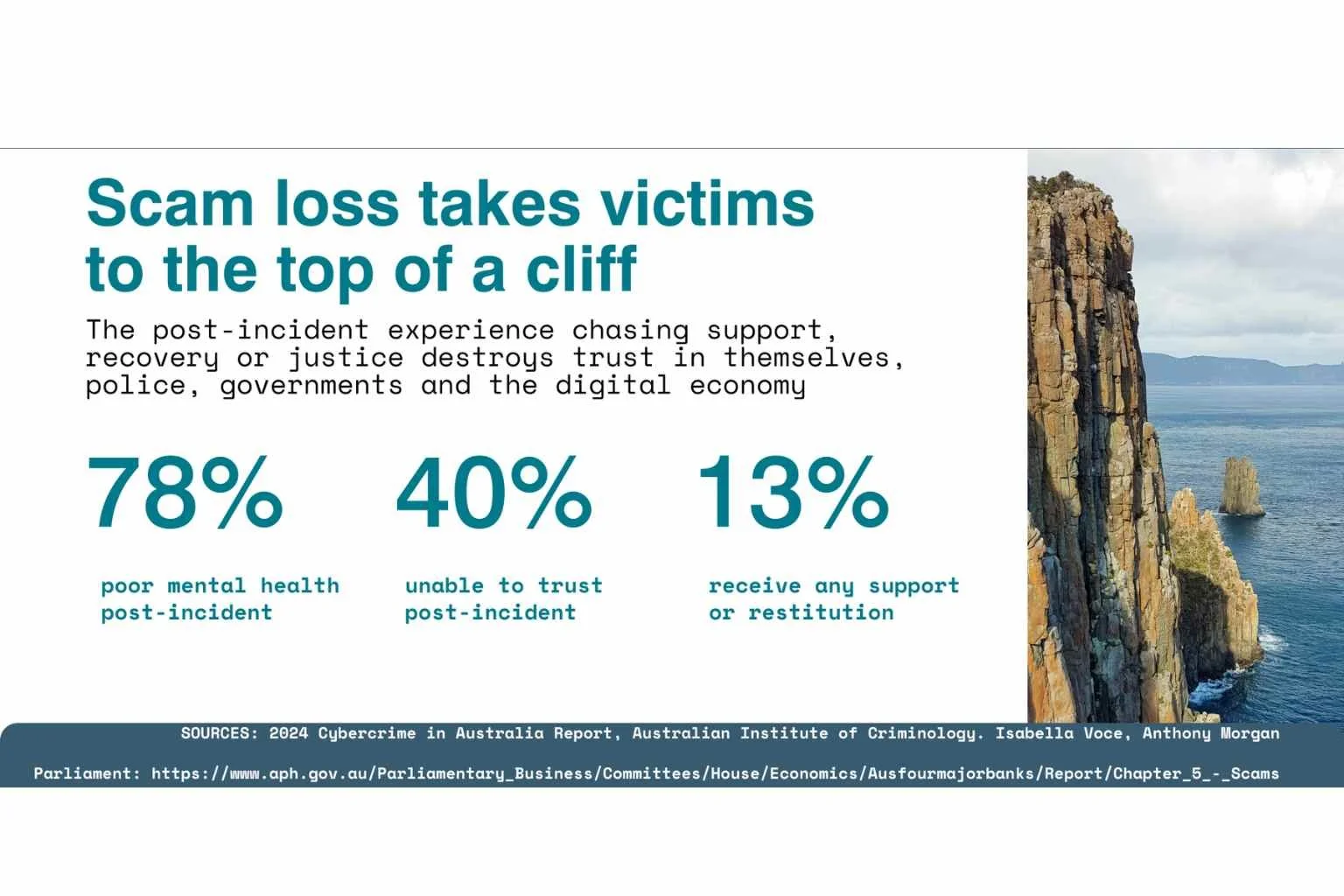

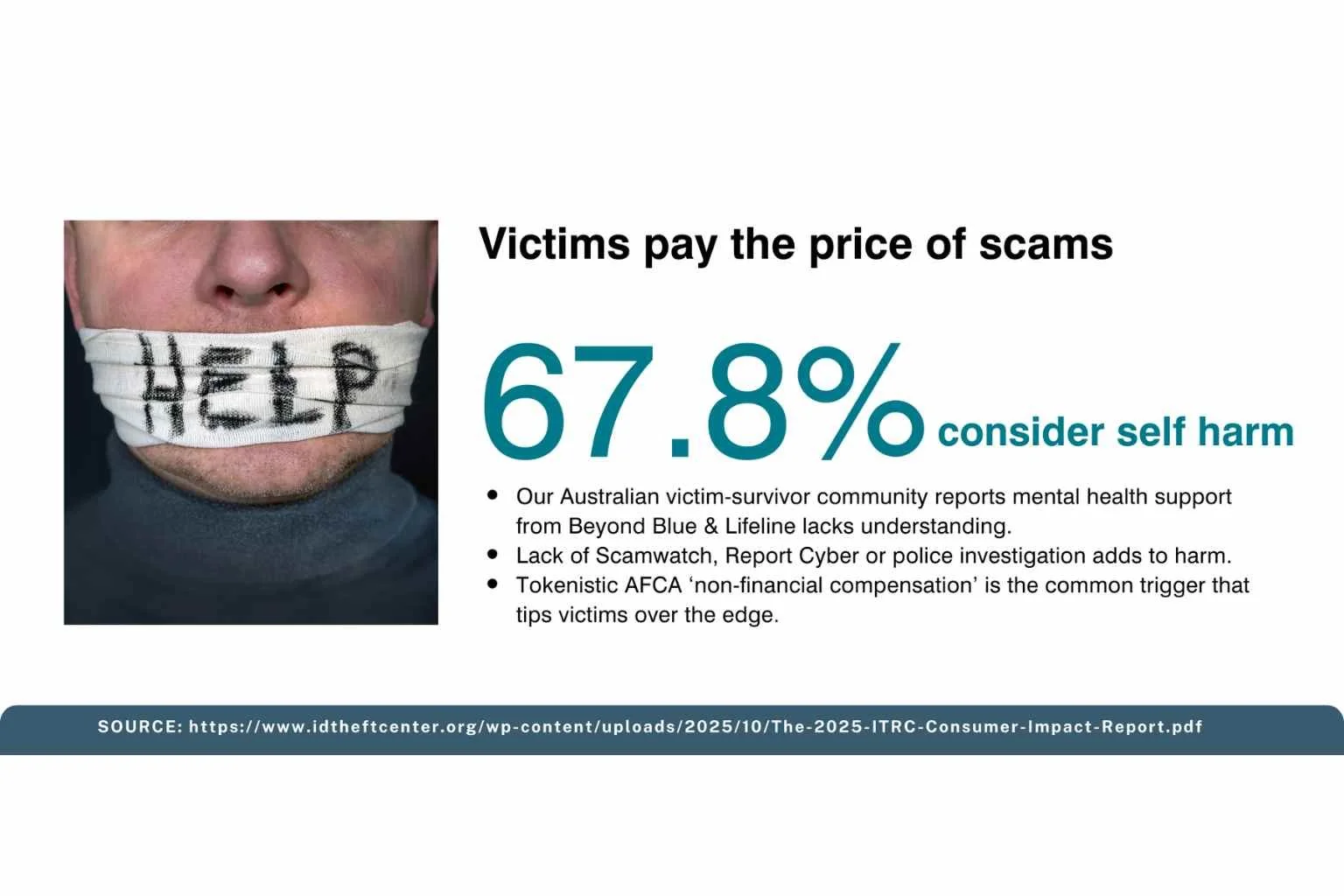

● And if just 70% of Australia’s estimated 1.25 million scam victims since 2021 required Medicare-funded psychological support, it would cost taxpayers approximately $1.24 billion in mental health care.

Our executive summary recommends key inclusions and designations to stop scams proliferating and make a genuine attempt to reimburse consumers.

These costs represent real and growing pressure on Australia’s public services, all while institutions that failed to prevent scam fraud are not held financially accountable.

In addition, we believe two critical failures have left Australians exposed to an untested legal liability that’s enabled large-scale theft from individuals through scams:

1.Banks have refused to acknowledge that their platforms and processes have been conduits for criminal fraud.

Banks have remained wilfully blind to their role in the fraud crisis, relying on the same strategies of denial used during the 2019 Royal Commission. Banks and payment platforms deflect from their facilitation of fraud (including impersonation and payer manipulation fraud) by insisting that scam losses are customers’ fault, even though banks have legal duties:

not to allow mule accounts to be established that don’t meet Know Your Customer (KYC) standards,

raise red flags for known scam patterns,

transparently recover scammed funds.

Banks spend millions marketing their “scam defences” and boasting about AI and staff investments — yet still blame customers when their own processes and failures to train staff on known scam typologies fail. Banks have ignored basic safeguards like 48-hour payment holds or MFA for high-risk transfers, such as property purchases or superannuation, and shifted the blame to customers rather than invest the paltry $100m needed to establish CoP before the fraud crisis escalated in 2020.

2. Regulators and Government failed to implement Confirmation of Payee (CoP) as part of the ePayments Code review early enough to protect Australians.

In 2019, Consumers Federation of Australia called out the lack of “meaningful sanctions to create an effective deterrent for non-compliance” in the ePayments Code, leaving Australians uniquely exposed to fraud. The ePayments Code - along with the Banking Code - are sometimes contentiously misinterpreted by an over-run External Dispute Resolution body, the Australian Financial Complaints Authority (AFCA).

In Part 2: Introduction of this submission, we outline how corporate failures have emboldened domestic fraudsters to escalate their tactics. In Part 3: Consultation questions we specifically explain the 6 key recommendations outlined in our Executive Summary below and in Part 4. Whole of ecosystem approach we offer our conclusions. Evidence for our recommendations is then provided in our Appendix items.

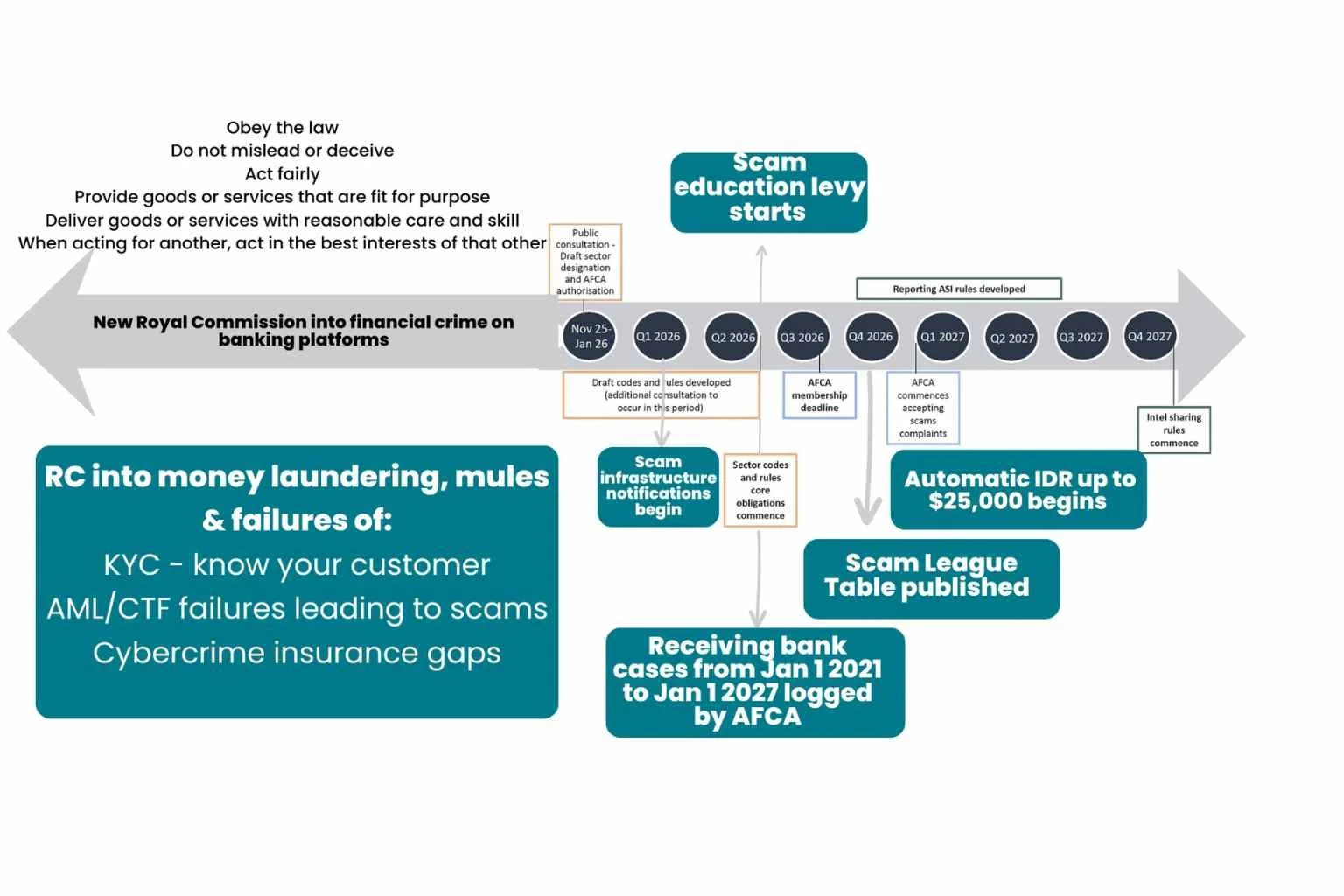

We welcome the draft Scam Prevention Framework (SPF) and newly published codes and designations which promised: “Victims will have clear pathways to compensation if the business fails to meet robust standards.” — Former Assistant Treasurer Stephen Jones on 13 February 2025 when he promised the SPF Codes would protect Australians and be operational from July 1 2026

Upon release of the designations from Treasury, analysis published in Australia’s leading financial newspaper stated:

“The definition of reasonable steps is rubbery enough to give the banks, telcos and social media platforms a “get out of jail free” card … Compounding that problem is the fact there will be no legally enforceable actionable scam intelligence for at least two years.” — Australian Financial Review’s Tony Boyd on 22 December 2025 about the newly released Treasury consultations and position paper this submission focuses on

SVA believes individual victims and taxpayers bear the cost of financial crime that corporations profit from. We believe the SPF designations must be significantly improved with 6 recommendations.

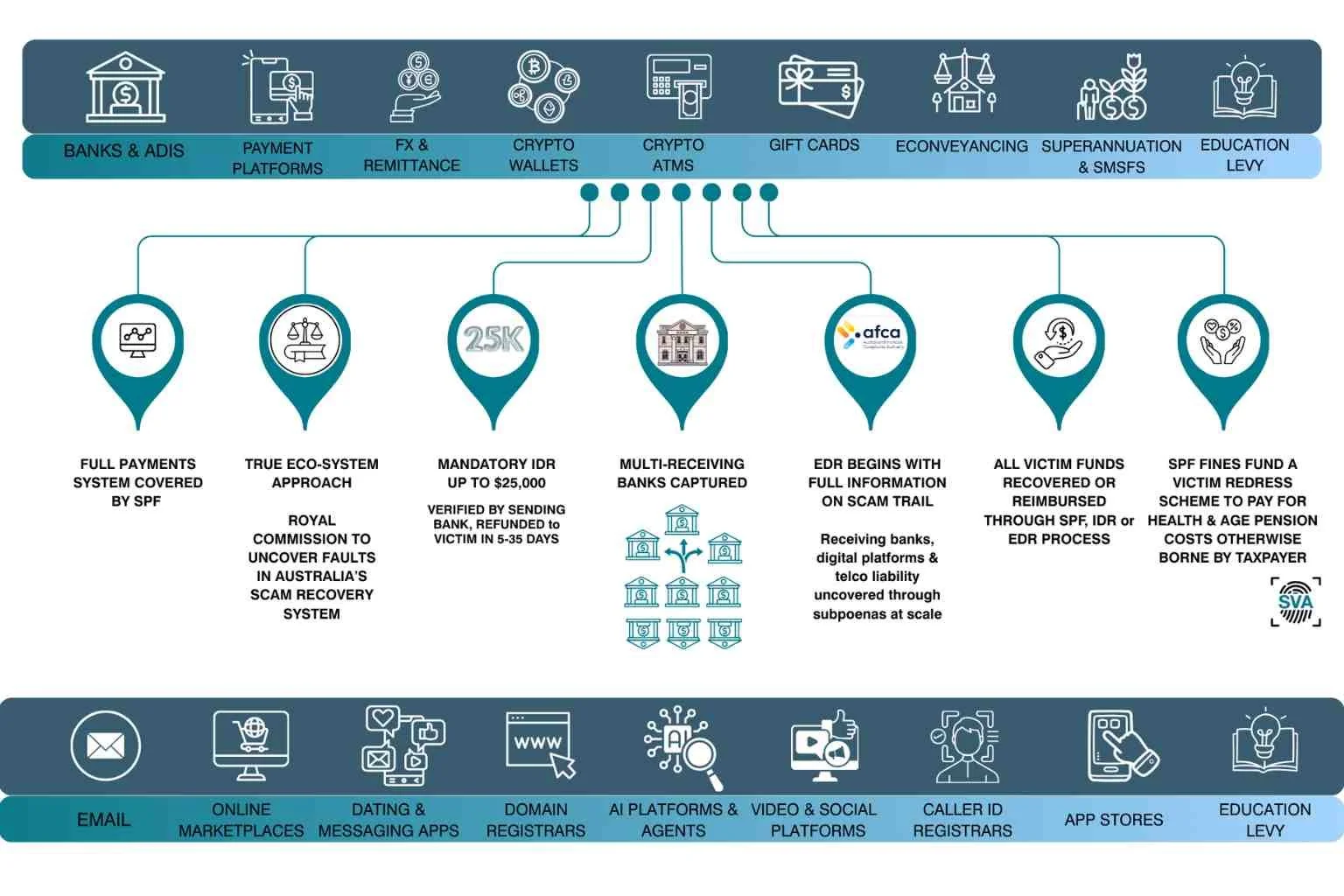

Recommendation 1. Governance works only if all entities in scam chains are designated

All relevant sectors must be designated under the SPF to ensure whole-of-ecosystem accountability and give the framework any chance of achieving its policy intent. This includes:

● Banking & Payments: All ADIs, non-bank remitters (especially foreign currency remitters such as Wise, Revolut or OFX), cryptocurrency exchanges and ATMs, eConveyancing platforms (PEXA and Sympli), gift card services, payment providers (BPay, PayID, Monoova, Cuscal, PayTo etc), and superannuation funds.

● Digital Platforms: Email hosts (e.g. Gmail, Outlook, Yahoo), online marketplaces (Meta, Gumtree, eBay), dating apps and platforms (Tinder, Hinge etc), domain registrars (e.g. GoDaddy, Ventra IP), Hosting platforms (e.g AWS or entities responsible for servers not serving illegal material), Caller ID registrants (e.g. Hiya), AI agents (e.g. ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini), App stores (side-loading malware is a key scam vector).

Furthermore, we believe that ASIC’s Registers and MoneySmart Investor warnings must be held to the same standard as the SPF dictates for regulated entities. Our community believes ASIC’s investor warnings have failed to keep up with known scam patterns and actively endangered people to invest in imposter and investment scams that could have been prevented through up-to-date warnings and a hotline to check for known scam types.

Additionally, an education levy should apply to designated sector ASIC registrations to fund a Safe Systems approach to scam awareness.

The SPF risks becoming a framework of good intentions that will actually increase scam harms unless the Codes impose clear and enforceable obligations on regulated entities.

The proposal for equal apportionment of scam-related compensation among institutions is problematic. Banks have historically borne the responsibility for safeguarding customer funds. Diffusing bank liability must be tied to demonstrated levels of responsibility and control failure—not arbitrarily split. Without enforceable standards and fair redress mechanisms, this framework will not only fail to protect Australians, it will entrench systemic gaps and allow industry actors to continue passing the cost of preventable fraud onto victims and taxpayers.

Recommendation 2. Prevent scams with a hotline and Scam Infrastructure League Table in advance of Actionable Scam Intelligence-sharing

A scam education campaign and consumer hotline should be funded through an ASIC levy on all SPF-designated entities or funded by proceeds of crime. Scam infrastructure reporting must begin in the first half of 2026 with the NASC publishing a Scam Infrastructure League Table, updated quarterly, listing the most misused corporate brands (including impersonations of government entities like the Australian Tax Office), mule accounts, phone numbers and scam ad, email and website tactics — with strict liability for entities failing to block repeated abuse. Consumers must be able to call a hotline to find out if they are paying a known scam account, receiving calls from a known scam number or receiving ads, emails or phone numbers from known scam compound devices or locations.

Furthermore, scam infrastructure data can already include existing intelligence like:

● Known mule accounts reported to Scamwatch, the Australian Financial Crimes Exchange, the Global Signal Exchange and state and federal law enforcement information,

● Known spoofed telephone numbers used in previous frauds investigated by ASIC,

● Known accounts flagged to AUSTRAC through SMR and TTR reports that are associated with other known scam typologies.

We would also contend that part of the harm to victims is not adequately measuring scam losses or how effective warnings and education campaigns are. We would also ask the Federal Government to find a better way to measure the taxpayer impost of looking after scam victims after losing life-changing amounts of money.

Recommendation 3. Detect by having sending banks as single ‘front door’ for whole-of-sector reimbursement, supported by regulators and law enforcement

Banks are best placed to act as the front door for scam reporting, verifying losses with their customers before collecting full scam infrastructure data (e.g. malicious ads, email headers, hosts of illegal content, mule accounts, fake domains, impersonated brands) to help detect patterns and trigger liability across non-bank sectors. Regulators and law enforcement would support this scam infrastructure reporting.

Recommendation 4. Report full scam payment‑trail disclosure to trigger a 5-35 day IDR reimbursement up to $25,000 with funds recovered from other SPF entities through infringement notices and court enforcement.

Banks must verify scam losses and pay up to $25,000 at IDR within 5–35 days. If a case is unresolved, regulators and law enforcement must subpoena the full scam trail - including scam infrastructure and receiving banks - before escalation to EDR or recovery from other sectors.

SVA recommends the full scam infrastructure trail must be subpoenaed quickly (ideally by day 36 after the scam report if mandatory $25,000 IDR reimbursement fails) to trigger early detection and disruption. Strict liability must apply to any entity that fails to block or shut down known scam infrastructure. All SPF fines should fund a victim redress scheme to fund ongoing reimbursement and mental health programs.

A separate ASIC scam education levy should apply to designated sectors and this education must be responsive and agile in the same way road safety campaigns and education adapts to high-risk road use trends. Education campaigns must be whole-of-sector focused and educate about corporate compliance culture, mule accounts and money laundering to prevent harm before it starts. This must include a free, language-supported telephone hotline for the public to check scam warnings and report suspicious activity — especially for vulnerable or non-digital consumers.

Recommendation 5. Disrupt by ensuring all telcos, digital platforms and banks have clear reimbursement, freezing and takedown obligations - backed by law enforcement

Fast, clear Internal Dispute Resolution (IDR) is the most effective way to stop scams in their tracks. When all designated corporations face a financial incentive—such as IDR up to $25,000 in reimbursement and larger penalties—they’ll act quickly to freeze and recover stolen funds. Fear of financial loss will displace the current wilful blindness, driving action desperately needed to protect victims and save taxpayers.

We believe a nationally co-ordinated approach like Australia has used to tackle road safety can be emulated to restore safety and trust to our digital economy, potentially by considering issues like:

Mandatory cybercrime insurance (like compulsory third-party insurance to register a car)

Fines and infringements issued by law enforcement to SPF entities (like speed camera or parking infringements - failure to pay results in heavier fines and criminal offences)

Education and targeted enforcement Additional ASIC levies on high risk SPF entities fund a scam hotline, with the National Anti-Scam Centre (NASC) publishing true and verified scam data that tells the public the truth about corporations’ role in scams — whether impersonated or genuine. We would also encourage public reporting of corporate investment in staff training around scams and month-by-month marketing spend.

Recommendation 6. Respond with a Royal Commission into financial crime with the 6-year common law protections to apply to receiving banks

A Royal Commission into financial crime, mule laundering and systemic failures is required to deliver accountability and lasting reform. SVA is concerned that the erosion of existing common law rights under the SPF (i.e. existing bank liability) is reduced from the pre-SPF 100% down to 50% or less if other SPF entities are involved, hence we demand the 6-year common law rule must apply.

We propose a Royal Commission is necessary to investigate how financial crime has infiltrated Australian financial services with so little reimbursement to consumers.